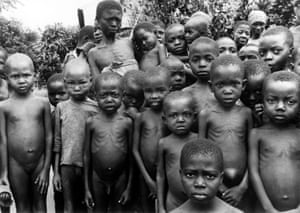

(FILES) In this file photograph taken on October 28, 1967, Nigerian federal army soldiers survey a police checkpoint on the west bank of the Niger River at Asaba, from where they launched an amphibian offensive on Biafra, during the Biafran war. – A civil war opposing Biafra secessionnist tribes fighting for independance and the federal troops killed between one and two milllion people, most from hunger and disease, from 1967 to 1970 in the Biafra region in south-eastern Nigeria. (Photo by Colin HAYNES / AFP)

IntroductionFifty years ago in the Bight of Biafra, the anger and love that created rivulets of blood that coloured the landscape of Igboland crimson and changed the concept of Nigeria as a nation ceased and changed to recriminations and a new battle for survival.

The Nigeria – Biafra War (also described as the Nigerian Civil War) of 6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970 was significant in Africa for the unfair political negotiations that started – and ended – it, as well as the allegations of genocide and failure of integration of Biafrans into the Nigerian polity after the war. The war also generated unprecedented media attention, dwarfing other conflicts, such as the war in Egypt, occurring around the same time. When the conflict began, the ‘police action’ quickly escalated to war with no formally identified front, involving many factions, including the Third Force, mercenaries and incidental soldier-journalists; it ended in a negotiated peace more noted for confusion and suppression than integration and progress. However, the most important outcome of the conflict has been the cultural shift in literary production.

The geographical area of Biafra was famous for the Onitsha Market Literature in the 1950-1960s. However, with the Nigeria-Biafra war (1967-1970), there was a shift in the focus of the literature from romance and politics to injustice and the portrayal of anguish. Many of the literature were still written by known and familiar writers, such as Cyprian Ekwensi and Chinua Achebe, but there were some new writers – Eddie Iroh, Elechi Amadi, John Iwuh and Ogonna Agu – whose anger created new cultural metaphors for the appraisal of the effects of the war.

This presentation is on the work of these younger writers, many of whom are dramatists, and their reading of new meaning into the post-Biafra/n universe, drawing materials from the politics and the angst of the war. This paper derives from ongoing research into drama produced during the war and promoted afterward. It draws heavily from a monograph that is currently under preparation.

FILES) In this file photograph taken on August 16, 1967, Colonel Odumegwu Emeka Ojukwu, the leader of the breakaway Republic of Biafra, stands in front of a Biafra flag as he addresses a press conference in Enugu. – A civil war opposing Biafra secessionnist tribes fighting for independance and the federal troops killed between one and two milllion people, most from hunger and disease, from 1967 to 1970 in the Biafra region in south-eastern Nigeria. (Photo by – / AFP)

Soldiering, Suffering and Soya Milk

My first knowledge of the war – even though I didn’t know it was war or that a conflict of that magnitude was going on – came through seeing soldiers speeding through the streets of my town in their military lorries. Some officer home on leave or some troops passing through. Somehow, I conflated the image of these soldiers with destruction and anguish; a few years before the war, several homes and industries had been burnt and destroyed during the political chaos of 1964, when the political parties turned the towns and cities in Western Nigeria to a battleground, aptly known as Wetie! (Douse it (him) in petrol and set it (him) alight). They had not yet been rebuilt. While the soldiers paraded along the roads, the chargrilled carcasses of these properties remained as memorials saluting their ego. Yet, for another reason, I was fascinated by these soldiers. I was fascinated by the crisp uniforms, the Land Rovers, the helmets, the boots and the proud bearing of the officers. We – my playmates and I – wanted to be nothing but these soldiers. They were our heroes. And we spent our days marching up and down in-between the houses, relieved only by mother’s calls to supper. Despite our misgivings at the sight of these soldiers, their presence seemed to bring a delicacy that was hitherto unknown to our palates. The soldiers always seemed to have an abundant supply of milk powder and another kind of powder that turned gooey in our mouths and which tasted strange – neither sweet, like the milk, nor savoury. To be candid, it probably tasted ghastly! It was later that I found out that the weird substance was Corn-Soya-Milk, also known as CSM or Formula Two, a newly devised relief food solely produced by the US Government, for the Christian missions to distribute to the starving children of Biafra (see Frederick Forsyth, The Biafra Story: The Making of an African Legend, Pen & Sword Military, 2007).

The problem was: we were not starving children of Biafra, we were not in Biafra, and the soldiers were not agents of the JCA, the Joint Church Airlift or the International Red Cross. Something was wrong here. Perhaps that’s why the powder tasted strange.

Of Refugees and Prostitution

My second intimation was a few months after the war. A community developed in an area between our house and the Methodist Cathedral, seemingly overnight. Shortly, around the Easter period, the place started filling up with rickety sheds and ramshackle structures made with wood planks and iron roofing sheets. The development had a strong impact on me, as the area was on the route I took to school, which was situated in the church compound, and we – my friends and I – had to find other routes that skirted the structures.

There was also something unusual about this new community: it was composed of only women and children. There were no men. Or at least, none that we could see. Naturally, we were curious about people. But nobody could understand the language and communication was therefore difficult and consisted of signs and a hybrid combination of Ìjèṣà (Yorùbá), Igbo and Pidgin English. However, the children mostly went to my school and gradually I became friends with some of them, even if they almost always slept during the morning hours and break periods. We spent the afternoons together playing games or sports in the school, and my friends often accompanied me home and shared our beds.

Gradually, we pieced the jigsaw together. Late-night activities at the now overcrowded Ìtisin quarters; children not getting enough sleep and having to sleep during the day; strong smells of alcohol and tobacco in the area; unexplained noises and fights whose causes we couldn’t fully understand. Yes, our childhood had changed forever.

My classmates, friends now, spent our play times telling us stories of the Biafra that never made it to the newspapers – the horror of death, the pain of injuries, the deprivation, the fleeing from one village to the other at night to escape both the federal soldiers and Biafran conscriptions and hiding in hastily dug pits, the hunger, the lack, and the resourcefulness imposed by the war.

What nobody mentioned were: ‘refugees’, ‘prostitution’, ‘rape’, ‘child abuse’, sexual exploitation’, ‘domestic violence’, ‘assault’, ‘genocide’, ‘kwashiorkor’, ‘hepatitis’, etc.

And it wasn’t long before the whole country started feeling the effect of the war and its aftermath. Unemployment, lack of security, armed robbery, violent burglary – all entered the lexicon of everyday words.

Sunset in Biafra and other Detention Stories

Six years after the end of the war, the government’s policy of reconciliation, rehabilitation and reintegration had run its course and the nation had all but forgotten about the war. The Missing notices in the newspapers had reduced to a trickle and everything had become normalised.

There are some things however that one can never forget.

Our writers and historians also made certain that we never forget.

One of the first records of events was a short play released in 1972, The Last Days of Biafra, by Thomas Orlando Iguh. This was published the same year as Wole Soyinka’s prison notes, The Man Died1. Last Days of Biafra was in pamphlet form, and the cyclostyled copies were circulated at the motor parks, market places or sold by newspaper vendors. Other plays written around the time include Ogali Ogali’s No Heaven for the Priest (1971), and Enough is Enough by Ene Henshaw (1976).

Iguh was a political writer of the Onitsha Market Literature tradition (although he also wrote a few love stories, e.g. Why Men Never Trust Women, The Sorrows of Love). Most of his writings were about African political leaders – Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, and Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria – and their lives and works. He was not unique in this; many of the Onitsha Market writers wrote a lot of political plays, novels, and poems. Iguh had become a household name with his publication in 1964 of Life and work of Dr. Zik in the Nigeria Republic, on the travails of Nnamdi Azikiwe and the fortunes of the NCNC, his political party, in the general elections. But Iguh’s work became enduring because of the Last Days of Biafra. It passes no judgment or blames. It simply recounts the history of Biafra from the Aburi Peace conference in Ghana to the occupation of a large swathe of Biafra by the federal army, leaving the people consulting the gods in search of peace, a possible reference to the final trip to Cote d’Ivoire by Biafra’s leader, Odumegwu Ojukwu to seek peace. Curiously, Iguh left out the symbolic surrender in Lagos of Col (General) Philip Effiong, the acting leader of Biafran army. Another relevance of the play is that it set a template for younger playwrights writing about the war.

Last Days of Biafra is of course not a piece that can be readily or easily performed – some of the characters, especially Major Nzeogwu and Col Emeka (Ojukwu), routinely have lines running into hundreds of wordcount – but, in the tradition of Onitsha Market Literature, designed to be read in groups and debated in street corners. It was propaganda for the injustice of Biafra.

The following year, 1973, Elechi Amadi came out with his war diary, Sunset in Biafra, which, according to him, “is not a story of the war; [but] an intimate, personal story, told for its own sake”.

Defending his reasons for writing the book, Amadi states:

… the path to full national maturity lies through the fearsome jungle of self-criticism, and the sooner we take to this path the better. There are those who would have no intimate chronicles, now or ever. They are wrong. What today is grim and agonizing may be amusing, even hilarious, tomorrow. Let us not deny posterity a good laugh.

Rather than presenting hilarious situations, however, Sunset in Biafra exposes the many injustices of the war, by and against Biafrans, and especially against the minority ethnic groups in the enclave, one of which Amadi belonged.

Amadi reveals the struggles for survival or those who were not Igbo, the majority Biafran group, and therefore considered ‘saboteurs’. He writes about his efforts to assist the State, his arrests and detention, and his later collaboration with the Nigerian government, and having to work under Colonel Benjamin Adekunle, the commander of the 3rd Marine Commando.

An interesting read. Nonetheless, it was a familiar account. I had heard similar and more graphic stories from my primary school friends.

Sunset in Biafra, however, achieved one thing: it pushed me towards searching out books and accounts of the war. And there were several of them in quick succession from novels, to memoirs, plays, and poetry – everybody wanted to render an account of the war. But every single writer proved the cliché wrong: the popular myth lied – there is nothing glorious about war.

Of Roses and Bullets

One of the most captivating of these post-war novels is Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s more recent Roses and Bullets (2011), the book that provides the first part of my title. It is also one of the most realistic of the Biafran war literature.

With its alluring fragrance and beautiful softness, the rose in bloom is riddled with sharp thorns. When that rose grows in the war front, the thorns drip with poison, turning dreams to putrid nightmares. Coming after a long tradition of literature influenced by the Nigeria-Biafra war, Adimora-Ezeigbo’s Roses and Bullets reminds us in gruesome details that the effects of those three odd years at the tail end of the 1960s still course through our collective veins as a people. The results still affect and direct our thoughts and actions. Our future has largely remained stunted, trapped in the shallow trenches of our consciousness.

Numerous, these novels, all of them filled with the pathos of war, the courage of the fighting forces, the resourcefulness of those left behind, the strategies for survival. The novels nourish our understanding of what happened during those dark months, more than the history books and the soldier’s diaries. Accounts like Cyprian Ekwensi’s Survive the Peace (1976), Isidore Okpewho’s The Last Duty (1976), Eddie Iroh’s Forty-Eight Guns for the General (1979), Toads of War (1979) and The Siren in the Night (1982); Festus Iyayi’s Heroes (1986), Buchi Emecheta’s Destination Biafra (1994) and Ken Saro-Wiwa’s Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English (1994) all narrate the experiences that continue to bring that war to every Nigerian parlour and bedroom, metaphorically and physically, through the upsurge of armed robbery, political chicanery, underdevelopment, and general distrust. We may even consider Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun (2006), which has been made into a film (2013) by Biyi Bandele. But none of the earlier published works attempted to dissect our minds with the psychological consequences of the war as Adimora-Ezeigbo has done in Roses and Bullets.

Nobody could doubt the right or competence of Adimora-Ezeigbo to write about the war. She lived through it; she lost three brothers; she was even a militia, and her experiences must have informed the creation of Ginika, one of the important personas in the novel. Additionally, she has written short stories and other works of fiction on the conflict, apart from her critical study, Fact, and Fiction in the Literature of the Nigerian Civil War (1991).

The novel does not deviate much from the basic formula of Biafran war literature – two lovers, Eloka and Ginika, desperately in love become separated by the war they could not understand or want to be part of, but a war that would end up defining their existence. While their relationship endured the war, it did not survive the peace that followed. This reminds us of the relationship between James Odugo and his wife in Cyprian Ekwensi’s Survive the Peace (1976) But Ezeigbo goes further than that: we are drawn into the divisiveness of war, the agony of dejection and equally the humanity that triumphs as a banner, waving away the pain and violence.

The two lovers find a link in drama, and after a series of performances to boost the morale of soldiers, they decide on marriage. Soon after though, Eloka joins the Biafran army, and later becomes a Captain, same as Nwakire, Ginika’s brother. Ginika herself, having trained as a militia, becomes a worker at the Relief Centre – her contribution to the war – a situation that bodes serious consequences to her future. The two men, with Ginika, display fervent and spirited humanity and maturity that lead to their destruction.

And destruction is an operative word in the novel. Every segment of the narrative renders the human soul practically numbed. Everything reminds us of the ‘primitive animal’ in us. For instance, in recounting the exodus of the Igbo people from the north after the pogrom that contributed to the war, Adimora-Ezeigbo paints a gruesome and macabre image:

“An open carriage filled with human debris. Ginika saw severed hands and legs chopped, lying like pieces of wood on the floor of the carriage; there were dead bodies that were whole but with deep gashes in different places – the neck, chest, and belly… her eyes caught the figure of a woman lying naked, disemboweled; a dead fetus was hanging from her abdomen, its umbilical cord still attached to its lifeless mother”.

Or: “in the open space lay the headless torso of a huge man clad only in black trousers”.

This could have been the description of the carnage at Ibuza, near Asaba, where the federal soldiers indiscriminately killed and burned civilians (see Destination Biafra), or the massacre at Aba General Hospital, where patients were dragged outside from their beds, shot in cold blood and set alight. Though Ezeigbo’s account above was before the war, she leaves us under no illusion that war is noble or that there was “no victor, no vanquished”, the dictum of the federal government after the war. A redundant expression, similar to the wartime “Go On With One Nigeria” slogan, an acrostic formed from the letters of the name of the Nigerian leader, General Yakubu Gowon. In reality, everybody involved in the war was vanquished.

Adimora-Ezeigbo’s language is brutal; the imageries punishing, gnawing our sensibility like a blunt knife exenterating a live specimen. The anguish fills us with despair; hauntingly, you cry for respite, but your curiosity gets the better of you. And the ending does not disappoint, though the twist transports you unwittingly back into the worlds of Cyprian Ekwensi and Ken Saro-Wiwa (Sozaboy). And you wonder: have we really survived the peace, as Ekwensi prayed more than forty years ago? Or are we still psychologically traumatised, fifty years on?

But it’s not all gory, for in the midst of violence, the future grows. Adimora-Ezeigbo indulges the romantic in her with brazen rendering of love, disvirginity, and sex. Yet, those images are also filled with metaphors of violence!

“The kisses they gave each other ignited a flame that engulfed them. She panted and clung to him, even as his fevered and moist lips set out on a passionate journey from her mouth down the smooth road of her neck. Enticed by the firm swell of her breasts, his lips paid homage to each honeyed fruit from Nature’s own garden… the climax was so intense and poignant that the wrench caused little or no anguish; her terror emptied in great delight”.

But the images that linger in the mind are not of the violence and sex. The images that remain and nourish our memories are those of the importance of family ethos, the ingenuity of creative endeavours and the fickleness of the human ego that provided the psychological balm against the war.

Roses and Bullets is a fascinating read providing a generous insight into the core of that gaping sore that continues to blight our socio-political universe. Realistic in its portrayal, and dispassionate and candid in its narrative.

In reading the novel, we notice one other certain thing: those who survived the war did so because they allowed the rose petals to envelop them in a cocoon of hope. They are not – as Uncle Ray, one of the major personas in the novel, says – “opportunists”, but humans engaged with their survival instincts, optimists with dreams of freedom. But they need to heal; the land must heal them, as it gently drains of the poison of war. And that is where Adimora-Ezeigbo’s novel proves different from the earlier novels – a soothing balm to the trauma of our existence.

Whilst novels provide graphic images of the war, dramatic works question and desperately search for answers, or in the words of Chinua Achebe, the quest to know where the rain “first began to beat” the people. Whilst the novels depict the reality of the war, plays written after the war query the illusions created by that reality.

Re-reading Reality and Illusion in Post Biafra Literature

One of the playwrights whose drama poignantly queries the illusions of the war is Ogonna Anaagudo-Agu, another veteran of the war.

Anaagudo-Agu was a student of English and Drama at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka when the war started. He enlisted, saw action at the Abagana sector under Biafran Major Jonathan Uchendu, as part of the Abagana ambush of the Nigerian army led by then Colonel Murtala Mohammed, on 31 March 1968. The ambush destroyed more than a brigade of Nigerian army and raised the morale of the Biafran soldiers. After the war, Anaagudo-Agu went back to the university to complete his education. He published seven plays, including The Last of the Biafrans (1996), Dance of the Deer (1998), The Return of a Night Masquerade (1998), I Fear for Kattie (2000), and Symbol of a Goddess (2005); all inspired by the war and informed by Igbo culture. He creates a cultural metaphor for assessing the effects of the war on the society; he queries the symbol of the nation – is Biafra relevant and was it ever relevant? Is Nigeria a country, and who should belong in it? What is the currency of membership? More urgently, he asks “why Biafra?”

The messages encoded in his plays reflect a vision anchored on the recognition of past mistakes to help in dealing with the mental and psychological anguish of the war. In this, Symbol of a Goddess employs illusions to test the reality of the post-war identities.

Symbol of a Goddess tells the story of Emenike, a Biafran war veteran, and his attempt at integrating into the new Nigeria. He is portrayed as being still patriotic to the Biafran cause, and he fails to accept that the idea of a Biafran nation had been lost. He, therefore, struggles to adjust to the reality of a war that had been fought and lost. Emenike pits himself against society; defying tradition by wearing the Ozo2 anklet despite being a single man who had not yet taken the Ozo title. In his mind, he lives in Biafra, a new nation; he refuses to recognise “Nigeria” and this hinders his integration into the post-war society. In his Biafra, traditional institutions such as marriage are obsolete. He spends his days dreaming of an eventual manifestation of Biafra, metaphorised as the masquerade Egbe Eyi Ugo.

Etymologically, the hawk/kite (egbe) is the archetypal animal associated with the face in Igbo cosmology and mystical thought. The hawk has well-renowned ocular abilities. Ugo the eagle or sacred vulture, on the other hand, is the mightiest bird. Here, the motif references a Hawk with the Sacredness of an Eagle, the cosmic vulture, one of several in the pantheon of Igbo deities, headed by Anyanwu, the Igbo solar divinity, and solar cult. Egbe Eyi Ugo, on a metaphysical level, represents the female force – Nne Nwanyi – as well as the supreme force of eternity and the ruler of everlastingness – the Spirit of Light and of the Rising Sun – which leads us directly to the Biafran symbol – the Rising Sun.

We can already see the metaphor being evoked by Agu, the playwright, here. Symbol of a Goddess presents a situation where we are given an insight into the psychological problem of socio-economic integration3 and cultural adaptation of a “man of flesh and blood”, living in the reality of defeat.

The play is about the war and the post- of it (in the postcolonial sense). For Emenike, the war has not ended; the battlefield has only shifted to the economic problems in the society, the neglect of the welfare of the “losers” – please, remember that there was “no victor, no vanquished” – the psychological trauma of those involved in the war, and the lack of rehabilitation of the entire Biafran region. He refuses to surrender into the reality, preferring instead the “rising sun” of the promised hopes of Biafra. In the end, the dream turns into a nightmare: devastation; children with acute malnutrition (kwashiorkor) roaming the villages; widows holding homesteads together; men disabled by the war; stalled and terminated education; forfeiture of property to the federal soldiers and their collaborators; “genocide” and ignored war crimes; etc.

For Anaagudo-Agu, Emenike represents the vast majority of Igbo youths who lost their identity and security in the 30-month war. The Igbo people had been convinced – and forced – into the war on the premise of living in a free, independent nation with unlimited opportunities for economic, social and psychological development. Emenike reminds us of Nwannekaenyi “Nnamdi” Kenny Okwu Kanu, the political activist and producer of Radio Biafra, who is seeking to actualise the mandate of Biafra as a nation through his Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) organisation.

It is instructive to note that Anaagudo-Agu is not the only playwright who is re-reading the Biafran reality and separating it from the illusions of the past. Other playwrights include Chukwuma Okoye (We the Beast, 1991), Oladele Oladeji (Toro, Yohauibo- Yen, 2011), Tenibegi Karounwi (pseudonym; Diary of a Poet, 2011), and John Iwuh (Birthright, 2011).

Coda

Fifty years on, the ideals of Biafra are possibly being encouraged into the psyche of the Nigerians who claim affinity to the area of the country as defined. For instance, the current agitation for the recognition of the reasons for the war and integration of the “Biafrans” into the Nigerian polity is probably one of the reasons for the discontinuation of teaching History as a subject in all Nigerian schools.